A new study from Western Michigan University has found that wastewater treatment plants could have a negative effect on PFAS levels.

A negative effect

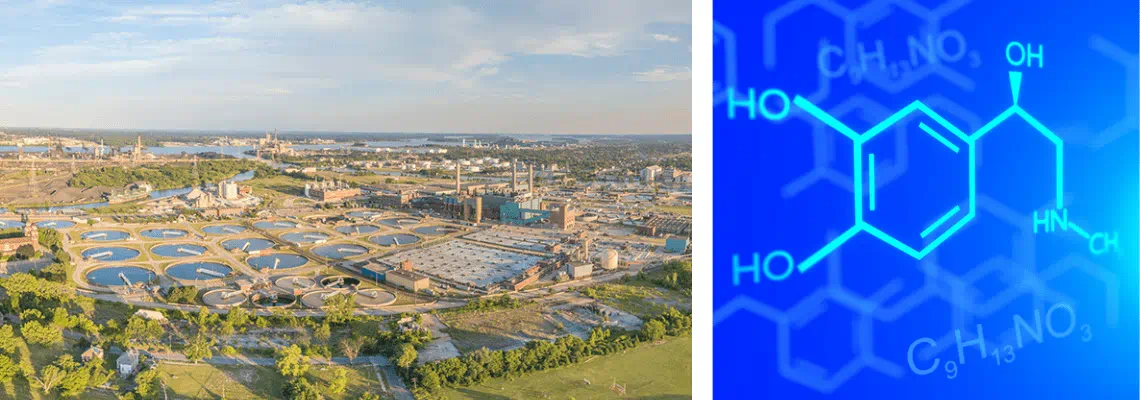

New research from Western Michigan University (WMU) suggests that treated water leaving wastewater treatment plants in Michigan has greater quantities of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) than the water entering.

The study, which was designed to highlight the complex cycling of PFAS, consisted of an analysis of 28 different PFAS compounds at 171 contaminated sites in Michigan by source release indicating four dominant PFAS sources: landfills, aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF), metal platers, and automotive/metal stamping.

In total, these accounted for 75 per cent of the contamination.

The study was carried out by Matt Reeves, associate professor of hydrogeology at WMU, Ross Helmer, an environmental quality analyst at the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE), and Daniel Cassidy, associate professor of Contaminant remediation at WMU.

“It can transform and change the molecular structure into some of the compounds that we can see.”

According to the study, it found that diverse chemical signatures were observed for leachates collected from 19 landfills. The dominant PFAS ranged from perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), to shorter-chained compounds, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFHxA), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFBA), and perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS).

The study attributes this to undetectable PFAS entering the plant are usually subjected to aeration and oxygenation inside the plant.

Speaking on Michigan Radio, Reeves said: "They can cause some of these compounds that we can't detect in the influent water. It can transform and change the molecular structure into some of the compounds that we can see.

"We are still trying to understand the transformations — whether there are microbes or not involved; something to do with oxygen or the lack thereof."

An in-depth study of 10 wastewater treatment plants in Michigan with industrial pre-treatment programmes found PFAS concentrations were at least 19 times higher in the plant's effluent or outflow than its influent.

One such plant that was monitored was the Great Lakes Water Authority, one of the largest single-site treatment facilities in North America, that services 2.8 million people in 79 communities in Detroit.

Just the tip of the PFAS iceberg

The state of Michigan currently has some of the strictest drinking water and groundwater standards in the nation.

The state's clean-up criteria are eight parts per trillion for PFOA and 16 parts per trillion for PFOS and have seven different PFAS compound regulations for drinking water.

In 2018, Michigan started the Industrial Pre-treatment Program (IPP) PFAS initiative requiring all industrial contributors to municipal wastewater treatment plants with IPPs to be identified and screened for PFAS.

“There is a whole host of these compounds that we know literally nothing about."

But recent studies have theorised that there may be 10,000 or more such man-made compounds in the environment, many created as unintended by-products.

"There is a whole host of these compounds that we know literally nothing about," Reeves said. "We only have toxicological data on an extremely small subset."

Currently in the US, there is a lack of federal policies on PFAS, with progressive utilities such as the Orange County Water District completing independent trials.

Last year, US Congress passed a bill for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to enact limits on PFAS chemicals in drinking water and declare them a hazardous substances.

Further study needed

While the study highlights what we currently know about PFAS being released from wastewater treatment plants, the Environmental Working Group (EWG) concedes that there is still a great deal of research to be done.

"[Reeves's study] really highlights what we just don't know, these are chemicals already in the system that are being transformed into compounds that we can actually detect," said Sydney Evans, an analyst for EWG.

"It's important that Environmental Protection Agency and the states look at these compounds as a class and regulate them that way."

One of the key barriers to driving new regulations and policies is raising awareness of PFAS and the systems that can prevent them.

Dr Cang Li, director of product development/QC at Kinetico, speaking to Aquatech Online said: "We may take care of one harmful PFAS chemical only to find another one later due to their extensive use in the world."

Point of use systems (PoU) is currently a hotbed of innovation for water companies to develop new methods of detecting and removing PFAS.

Further study is needed to identify PFAS pollution but what is clear from this study is that the PFAS challenge isn’t going away anytime soon.

- The full WMU study can be read here.

Related content

- PFAS certification in the US: the lay of the land

- Tech dive: the point of use systems taking on PFAS

- Jason Dadakis on OCWD's PFAS removal pilot

- Keith Hays: mapping the PFAS iceberg