How does wave-powered desalination work?

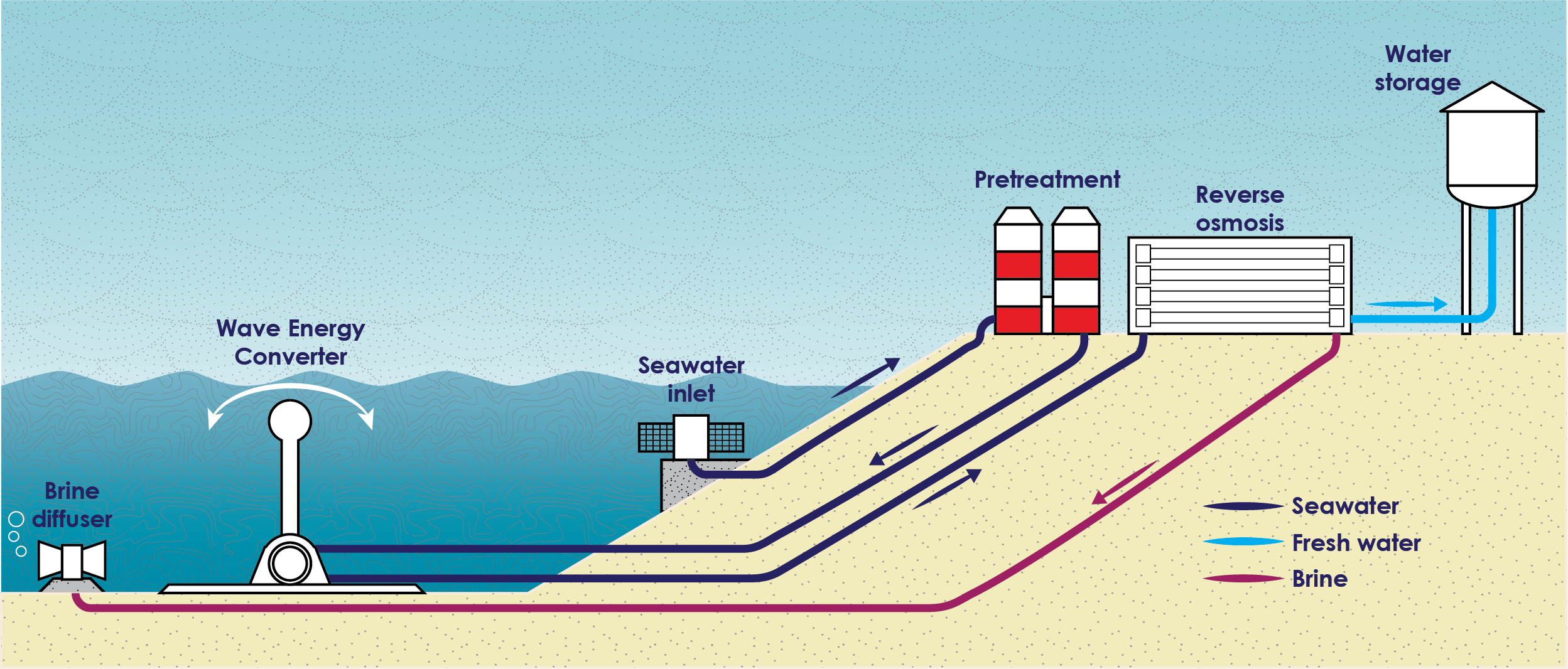

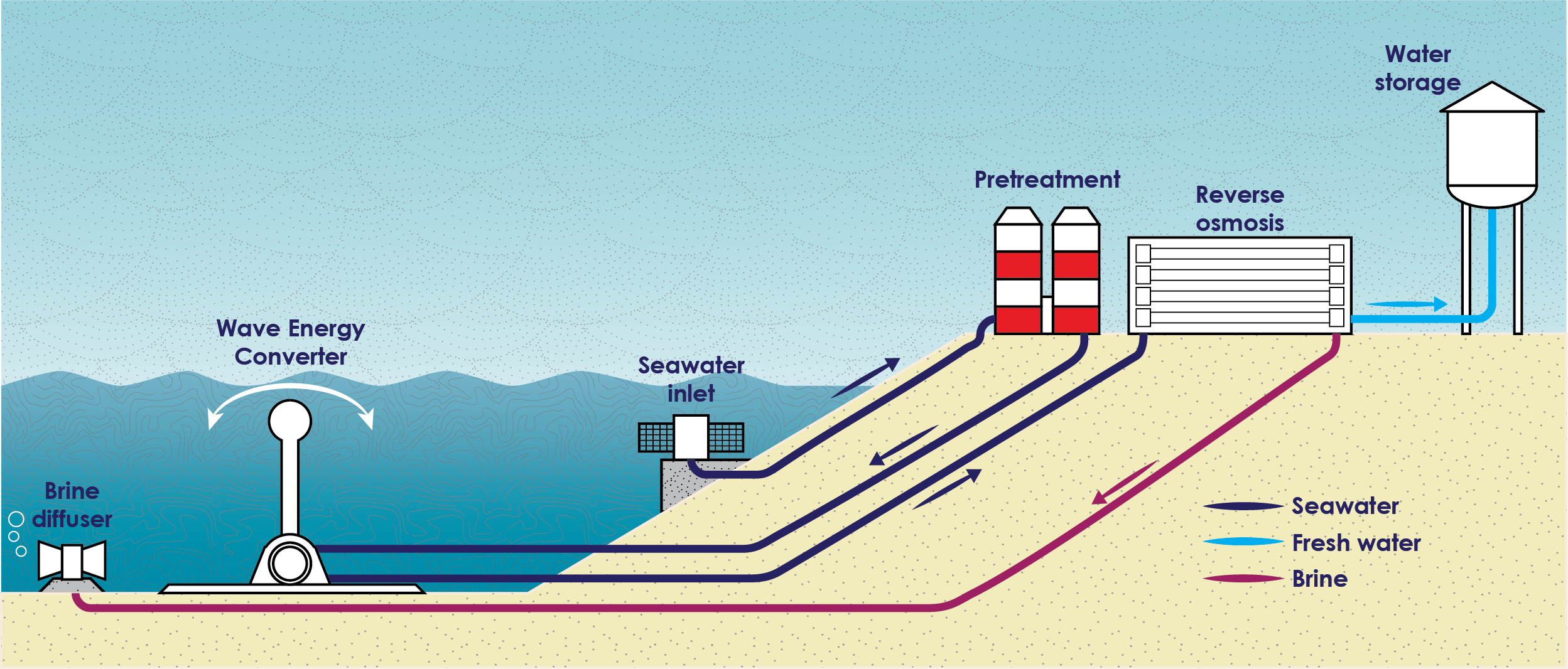

Several wave energy converters (WECs) pressurize seawater, which is then piped ashore to directly drive a seawater reverse osmosis (RO) desalination system.

Simply put: a series of paddles are moved forwards and back by the waves and the resulting energy is then harnessed to filter seawater.

The main feature, according to Ceberio, is that it uses “no electricity in the manufacturing process”.

Optimal wave height for Wave2O is between 0.5-3 metres, and the system is deployed near to the proximity of the shore, so that “it can be easily maintained”, said the COO.

System capacity ranges from 500 cubic metres of water per day at the lower end, right through to 4,000 cubic metres at the largest. This can meet the water needs of 5000 people, right the way through to 40,000, respectively.

Estimates show the cost to produce one cubic metre of water is $1.25.

Cape Verde roll out

Wave2O was initially tested in North Carolina, with the goal to roll out the first system to Cape Verde, an island country spanning 10 volcanic islands in the central Atlantic Ocean.

Implementation has been slated for 2020-2021 following a partnership secured with the Cape Verde Ministry of Finance and a $930,000 grant awarded by the African Development Bank hosted Sustainable Energy Fund for Africa (SEFA).

“Cape Verde is an ideal location for us: it’s one of the driest countries in the world,” added Ceberio. “It has no river or aquifers, limited rain and most of the water is already desalinated. Because it’s an archipelago, they have to import all of the oil to drive the desalination system.”

The COO claims the Wave2O can produce equivalent desalinated water for a third of the price of current production on the islands.

Despite securing funds from the US Department of Energy and other investors, the company said it still requires a total of $9 million in investment to move forward with its future growth plans.

Choppy waters for wave desalination

Aside from Resolute Marine Energy’s efforts, other companies around the world are working on wave-powered desalination methods as a cheaper, flexible alternative to centralized infrastructure.

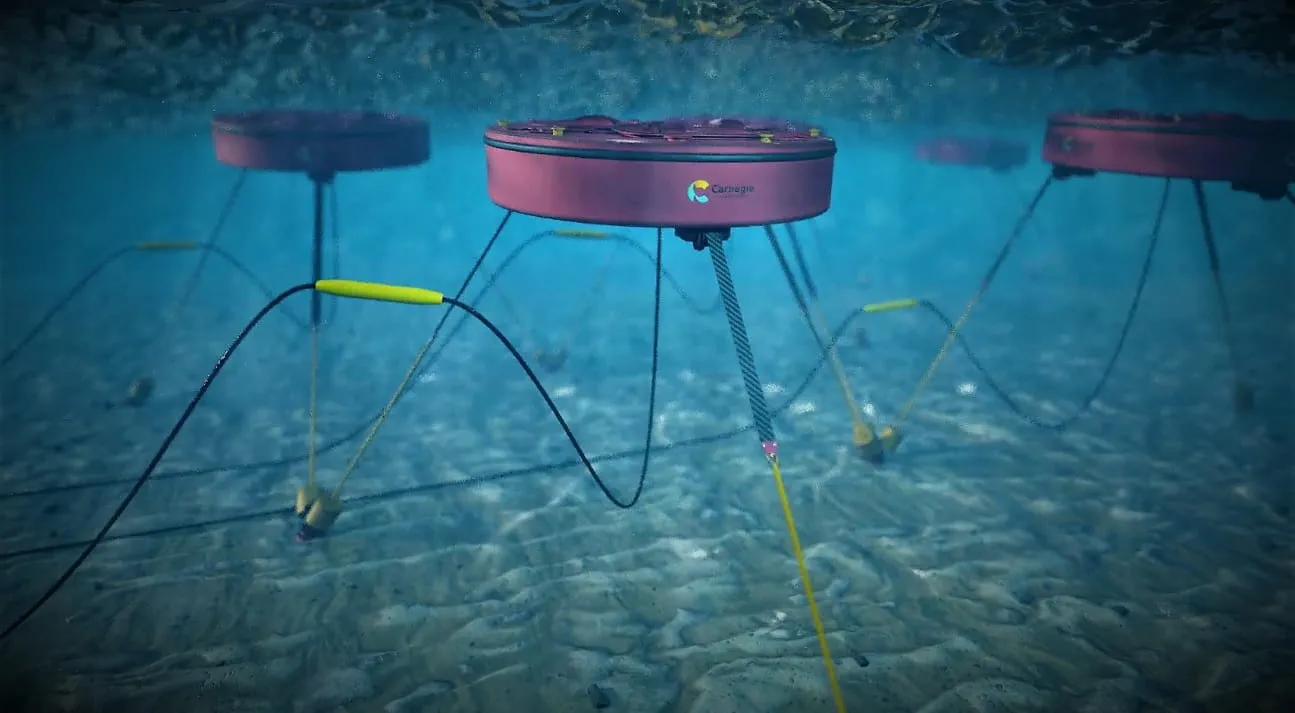

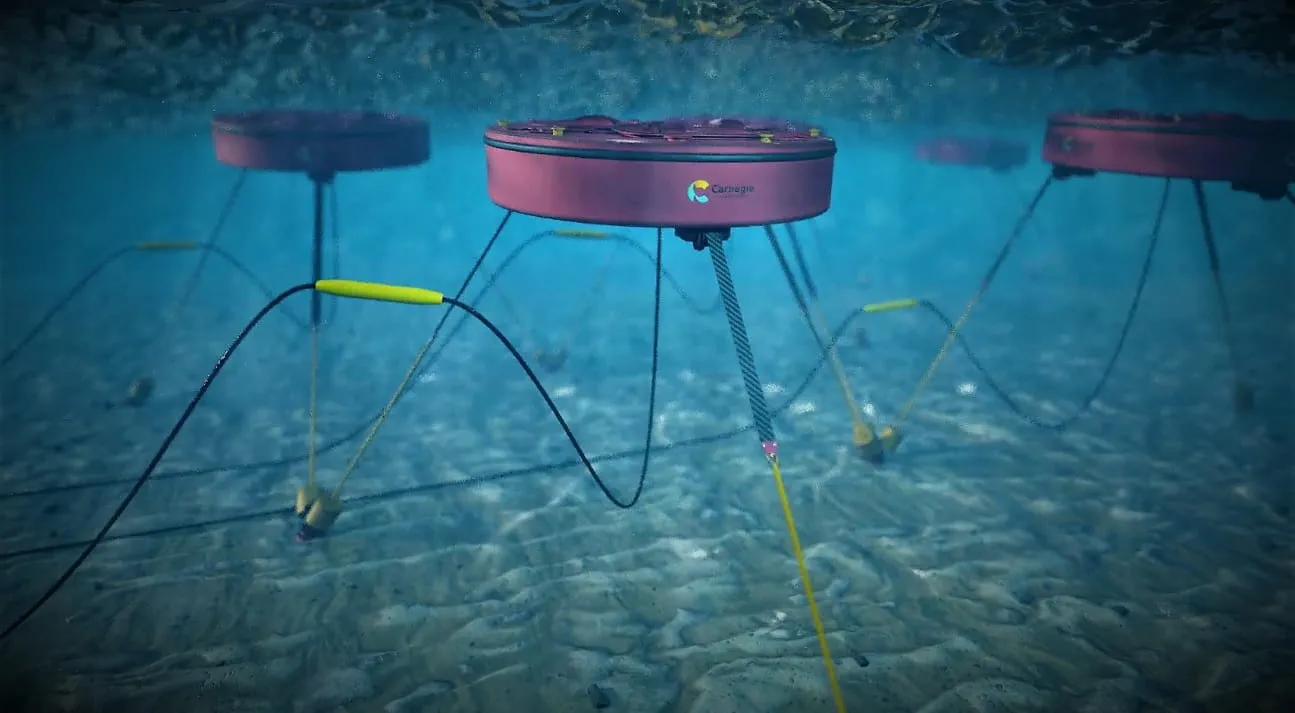

Australian company Carnegie has faced challenges scaling up its CETO technology, named after the Greek sea goddess. The IP was first lodged by the company in 2013, and the technology is now on version six.

Rather than being ‘fixed’ to the seabed floor, like the Wave2O paddle system, the CETO instead takes the formed of a submerged buoy that sits a few metres below the surface of the ocean.

Ocean energy is then used to drive a power take-off (PTO) system to convert the motion into electricity.

Carnegie claims it is the “only company to have operated a grid-connected wave energy array over four seasons” yet has faced significant challenges.

Despite successfully deploying its 5th generation CETO technology off the coast of Garden Island, the failure of microgrid subsidiary Energy Made Clean (EMC) left the company without sufficient funds to complete the project.

According to Renew Economy, this resulted in the Western Australian government terminating an AUD$16 million contract to build a wave farm off the coast of Albany.

ABC News of Australia referred to the “Perth-based renewable energy darling” facing once-loyal supporters to question “whether it’s time to stop pouring money into the dream of wave energy”.

Carnegie did not respond when asked to comment.

Related content